Dijkstra’s Algorithm¶

The algorithm we are going to use to determine the shortest path is called “Dijkstra’s algorithm.” Dijkstra’s algorithm is an iterative algorithm that provides us with the shortest path from one particular starting node to all other nodes in the graph. Again this is similar to the results of a breadth first search.

To keep track of the total cost from the start node to each destination we will make use of the dist instance variable in the Vertex class. The dist instance variable will contain the current total weight of the smallest weight path from the start to the vertex in question. The algorithm iterates once for every vertex in the graph; however, the order that we iterate over the vertices is controlled by a priority queue. The value that is used to determine the order of the objects in the priority queue is dist. When a vertex is first created dist is set to a very large number. Theoretically you would set dist to infinity, but in practice we just set it to a number that is larger than any real distance we would have in the problem we are trying to solve.

The code for Dijkstra’s algorithm is shown in Listing 1. When the algorithm finishes the distances are set correctly as are the predecessor links for each vertex in the graph.

Listing 1

from pythonds.graphs import PriorityQueue, Graph, Vertex

def dijkstra(aGraph,start):

pq = PriorityQueue()

start.setDistance(0)

pq.buildHeap([(v.getDistance(),v) for v in aGraph])

while not pq.isEmpty():

currentVert = pq.delMin()

for nextVert in currentVert.getConnections():

newDist = currentVert.getDistance() \

+ currentVert.getWeight(nextVert)

if newDist < nextVert.getDistance():

nextVert.setDistance( newDist )

nextVert.setPred(currentVert)

pq.decreaseKey(nextVert,newDist)

Dijkstra’s algorithm uses a priority queue. You may recall that a priority queue is based on the heap that we implemented in the Tree Chapter. There are a couple of differences between that simple implementation and the implementation we use for Dijkstra’s algorithm. First, the PriorityQueue class stores tuples of key, value pairs. This is important for Dijkstra’s algorithm as the key in the priority queue must match the key of the vertex in the graph. Secondly the value is used for deciding the priority, and thus the position of the key in the priority queue. In this implementation we use the distance to the vertex as the priority because as we will see when we are exploring the next vertex, we always want to explore the vertex that has the smallest distance. The second difference is the addition of the decreaseKey method. As you can see, this method is used when the distance to a vertex that is already in the queue is reduced, and thus moves that vertex toward the front of the queue.

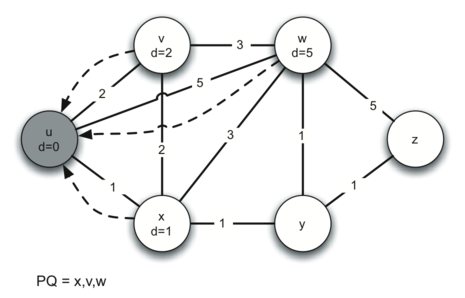

Let’s walk through an application of Dijkstra’s algorithm one vertex at a time using the following sequence of figures as our guide. We begin with the vertex \(u\). The three vertices adjacent to \(u\) are \(v,w,\) and \(x\). Since the initial distances to \(v,w,\) and \(x\) are all initialized to sys.maxint, the new costs to get to them through the start node are all their direct costs. So we update the costs to each of these three nodes. We also set the predecessor for each node to \(u\) and we add each node to the priority queue. We use the distance as the key for the priority queue. The state of the algorithm is shown in Figure 3.

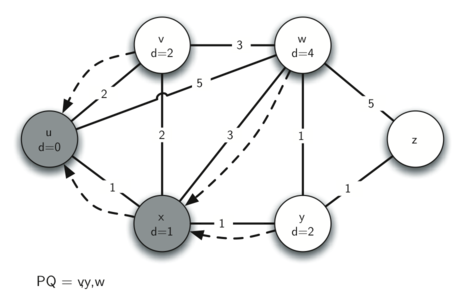

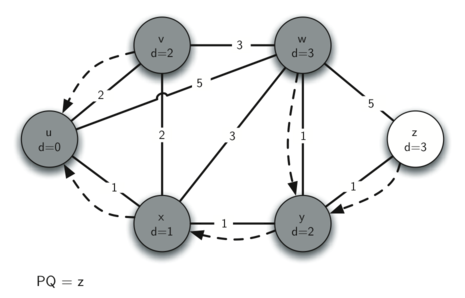

In the next iteration of the while loop we examine the vertices that are adjacent to \(x\). The vertex \(x\) is next because it has the lowest overall cost and therefore bubbled its way to the beginning of the priority queue. At \(x\) we look at its neighbors \(u,v,w\) and \(y\). For each neighboring vertex we check to see if the distance to that vertex through \(x\) is smaller than the previously known distance. Obviously this is the case for \(y\) since its distance was sys.maxint. It is not the case for \(u\) or \(v\) since their distances are 0 and 2 respectively. However, we now learn that the distance to \(w\) is smaller if we go through \(x\) than from \(u\) directly to \(w\). Since that is the case we update \(w\) with a new distance and change the predecessor for \(w\) from \(u\) to \(x\). See Figure 4 for the state of all the vertices.

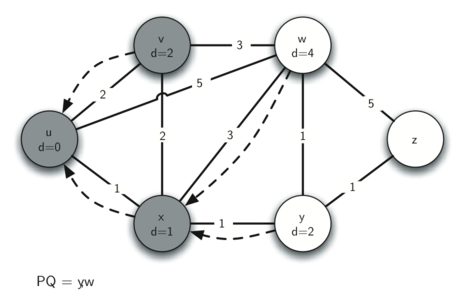

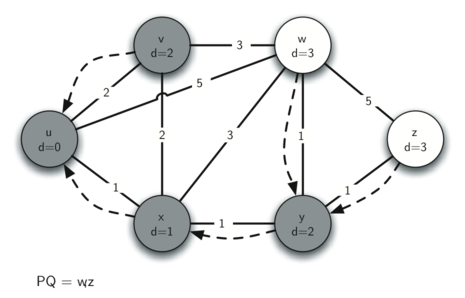

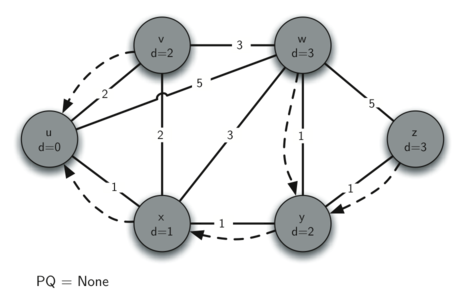

The next step is to look at the vertices neighboring \(v\) (see Figure 5). This step results in no changes to the graph, so we move on to node \(y\). At node \(y\) (see Figure 6) we discover that it is cheaper to get to both \(w\) and \(z\), so we adjust the distances and predecessor links accordingly. Finally we check nodes \(w\) and \(z\) (see see Figure 6 and see Figure 8). However, no additional changes are found and so the priority queue is empty and Dijkstra’s algorithm exits.

Figure 3: Tracing Dijkstra’s Algorithm

Figure 4: Tracing Dijkstra’s Algorithm

Figure 5: Tracing Dijkstra’s Algorithm

Figure 6: Tracing Dijkstra’s Algorithm

Figure 7: Tracing Dijkstra’s Algorithm

Figure 8: Tracing Dijkstra’s Algorithm

It is important to note that Dijkstra’s algorithm works only when the weights are all positive. You should convince yourself that if you introduced a negative weight on one of the edges to the graph that the algorithm would never exit.

We will note that to route messages through the Internet, other algorithms are used for finding the shortest path. One of the problems with using Dijkstra’s algorithm on the Internet is that you must have a complete representation of the graph in order for the algorithm to run. The implication of this is that every router has a complete map of all the routers in the Internet. In practice this is not the case and other variations of the algorithm allow each router to discover the graph as they go. One such algorithm that you may want to read about is called the “distance vector” routing algorithm.